FREE DOWNLOAD PDF

Note from the author

I wrote this first book in the fall of 1978 and finished it at the beginning of 1979, in the early morning between 4 and 8 o'clock every morning for several weeks. I still remember walking from my rooming house on William Street in Sillery to the National Assembly where I had a journalist's office.

I first wrote the manuscript on the back of sheets of paper on which were printed the transcripts of the debates of the National Assembly. I then rewrote my manuscript a few times to correct it and finally I had it printed on the photocopier of the secretariat of the Tribune des journalistes, in 100 copies for private distribution, but also to try to have it published by a real publisher.

I remember in the winter of 1979 that the publisher and founder of Éditions de l'Homme, Jacques Hébert, had invited me to his office in Montreal to discuss a possible publication.

In the end, he decided otherwise, but he encouraged me to continue writing.

It's a small world and I would later meet again, in March 1986, the same Jacques Hébert who was on hunger strike as a senator in Ottawa to protest for the reinstatement of the Katimavik program that the government was proposing to abolish and which he had created. I had become one of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's press secretaries...

The manuscript I am presenting here is the original version as published in 1979. There are several spelling and stylistic errors in the text, but I did not want to correct them in order to reflect the time when I was 22 years old and had no formal education.

If my thinking is naïve and a bit conquering in style, it is because of my age but also because at that time I had succeeded, despite all the obstacles and the lack of means, to join the best journalists of the Quebec Parliamentary Tribune and, for me, nothing was impossible! I was filled with the dream and hope of youth.

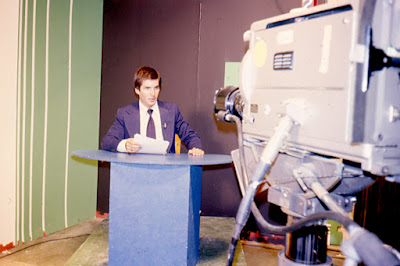

I was convinced that nothing, absolutely nothing could stop me. My dream at the time was even to one day replace the star host of Radio-Canada television, Bernard Derome. Obviously, this never happened, but the dream did exist and, in the end, that's what's important, because a life without dreams is no life at all! And sometimes, if we are lucky and destiny is there, our dreams come true!

This book is finally a kind of diary of the thoughts of the young man that I was at the time in the years 1977 to 79.

If I wanted to immortalize it with the internet, it is because this document is the first one that I will have written and it tells in detail my journey from my childhood to my early twenties.

Today in 2018, far from my 20s, I know well that we do not change the world, but that it is the world that changes and changes us. However, one must have seen time pass to understand this reality.

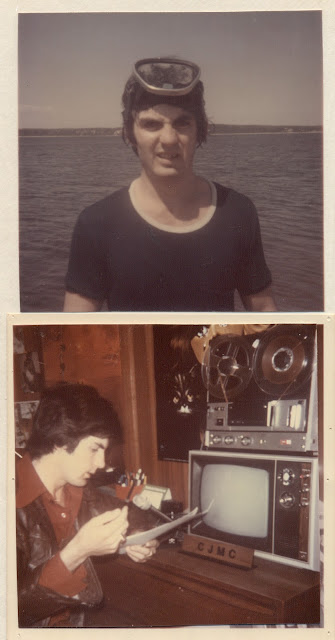

At the end of the text, a photo album has been added, which illustrates the story of the book. These photos were not published in the original edition.

Enjoy your reading!

Bernard Bujold - February 2018

|

| My office as a journalist at the National Assembly where I wrote the manuscript of this book in 1978 |

|

| Archive of the first pages of the book in original version |

______________________________________________________________

How I became a journalist at the National Assembly of Quebec? By Bernard Bujold (1979)

______________________________________________________________

PREFACE Journalism is a strange discipline!

It has been described as a social power capable of manipulating people and their ideas into acting in a certain way. It has also been said that journalists are good-for-nothing people from various, mostly bad, strata of society, and that these people do journalism because they are unable to do anything else to earn a decent living. What is the truth of this? I don't know yet, except that I find myself, at just over 20 years of age, a journalist at the Quebec National Assembly whose role is to monitor and interpret the actions of politicians, civil servants and the entire government of the province. How well do I do this job? Difficult for me to answer, but according to my bosses the answer is yes. Bosses who have to control media that serve nearly a million listeners either on radio or television. This is my story and the description of the whole path I had to follow to become a parliamentary correspondent. However, before I start telling you about my personal journey, I would like to dedicate this book to all the young people who will read it and tell them that even today it is possible to achieve things that at first seem impossible.

Hope, hard work and, above all, the courage to face obstacles can turn any difficulty around.

I would even go so far as to say that: "Impossible is not a word, neither in Quebec nor in Canada. "

I wrote this book for publication in a closed circuit and therefore those who will read it are usually my personal friends or members of my own family. I did not try to hide the facts or to be humble. Most of you already know my story, but without the backstory. In this book you will see how I have been able to achieve this or that success; successes that are actually of little importance to the great mass of the population. I want this book to have a personal stamp and to those who will have the privilege of receiving a copy, I say: "Keep it as a souvenir and tell yourself that it is a friend of yours who is the author and that he hopes to keep you as a friend during his whole life.

_______________________

CHAPITRE UN

Origines familiales

CHAPTER ONE

Family origins

Bernard Bujold was born in the Gaspé Peninsula in Saint-Siméon de Bonaventure, a small village of barely 1500 souls. It is Léonard Bujold, also a Gaspesian of origin, who on June 28, 1956, was able to contemplate the birth of his first son. Two years earlier, in August 1954, he had married Anita Cyr, a young girl from a village located a few miles west of Saint-Siméon, New-Richmond, a strongly English-speaking town. The couple would have two more children, boys named André and Raynald, but they would have to wait a few years later in 1961 and 1962.

Note that Léonard had already been married to Gemma Poirier, daughter of Benoit Poirier of Bonaventure, but this first wife died in 1952, one year after the marriage, leaving no children of the union.

Léonard Bujold was not an intellectual. He lived well, but modestly, on a rural property that also had farmland which he did not cultivate. He earned his living and that of his family by working for the almost unique industry of the area, today called Consolidated Bathurst of New Richmond, but at the time it was another group of industrialists who owned it. He did just about every job from lumberjack to labourer to maintenance man, in addition to maintaining his various personal properties.

His wife Anita Cyr was not a very public woman either. She preferred to stay at home and take care of the housekeeping. The couple was a good couple and lived simply like most other families in the neighborhood.

Bernard's childhood took place in this rural environment and was relatively comparable to that of any other boy who came from and lived in Gaspésie. The difference is that in his case his parents followed him very closely and spoiled him a lot. He was their only son, the couple Léonard and Anita were to have their other boys only in 196I and 62 when the eldest would be 5 years old, and thus like any only child he was overprotected by his parents.

He received his first primary education at the convent of Saint-Siméon which was at that time under the administration of a congregation of Ursuline Sisters. According to the nuns, Bernard had certain abilities, mainly in verbal elocution, which they used during amateur theater sessions. Apart from oratory, Bernard was quite skilled in the assimilation of the various subjects taught such as French, mathematics, history, religion, etc. He was almost always first in his class.

Almost always at the top of his class, those around him recognized the fact that he was gifted and that he would probably occupy, once he became an adult, some important function.

In his seventh grade year, Bernard was elected president of his class. Organized in the same way as a universally elected board of directors, the class had appointed a board of directors. The idea was originally conceived by the head of the grade, Sister Angeline Bourdage, who wanted to introduce the older students of the convent to organized social life.

At first, the students were reluctant and very few seemed to really want to get involved in the game. Sister Angeline had explained that the interested parties would have to go through all the stages, i.e. place their name in the running, make their little political speech in a sufficiently convincing way so that the other students would agree to vote in their favor and finally of course there was the official selection vote.

For his part, Bernard had not hesitated to put his name forward and he even put a certain amount of energy into his speech in which he invited his colleagues to nominate him for president. If they agreed to do so, he promised to help them organize a well-supported group life and made various projects seem interesting. Seeing such a zealous candidate for president and getting directly involved in Sister Angeline's game, some of the other children decided to do the same.

Eventually the position of president was given to Bernard and a leader was appointed for each of the other positions to be filled: secretary, treasurer and advisors.

During his term as class president, our young president took care of the organization of the group's life at school as he had promised. Among other things, he organized, with the help of the Sister in charge, an end-of-year trip where the whole class went on a tour of the Gaspé Peninsula. During the year as such, he had, with the help of the other members of the council, seen to the unfolding of various projects such as the student carnival, the art exhibition workshops as well as various other events of the kind.

In fact, Bernard's attitude during this school year was almost identical to that of the previous six years. He was a studious student and a sort of intellectual leader for the other children. He was regularly at the top of his class and was fascinated by studying to a greater degree than his classmates.

The atmosphere in which he was brought up may also have favored this behavior, for it must be said that if his family environment was rural and comparable to that of the other children, in his case there was a customary frequentation of the religious world. His mother's sister, Emilia Cyr, was the servant of the parish priest of Saint-Siméon at the time, Canon Alphonse Miville. Strongly involved in the liturgical life of the Gaspé Peninsula, Canon Miville, Mr. Miville as he was known among his friends, liked Bernard. His sister, Louise Miville, who also lived in the presbytery, was not without regard for the young nephew of the servant. All three of them, including Émi1ia Cyr, spoiled their protégé to the best of their ability and occasionally tried to interest him in religious life. Louise Miville in particular hoped to see him one day enter the clergy and become a priest. This social environment was certainly favorable for Bernard and even if he did not become a village priest, his childhood was marked by it and he kept many lessons for his adult life.

In addition to spoiling him, the Mivilles would often have him over for dinner, at lunchtime during school days, or would use his services to do minor repairs to the summer cottage, work that was done with the participation of his father Léonard who acted as foreman of the operations. It was even at the Mivilles' that Bernard earned his first real pocket money.

After his seventh year, at the end of the school calendar, important changes in his personality transformed him completely. As he moved from elementary to high school, Bernard gradually began to lose interest in school subjects. He lost interest in leading the group and whatever civics and manners he possessed he used almost overnight, as if he had disowned them. During the three and a half years that he spent in high school, this rejection of social respect became more and more pronounced. For his eighth grade education, he was able to continue to attend the convent in St. Simon, but when it came time for his ninth grade he had to go to Bonaventure, a small village some five miles east of St. Simon, on a daily basis.

This was the time when the government was beginning to centralize the students and the famous polyvalente fashion was approaching. Bernard's grade nine debut was even worse than the previous year. At the end of the calendar, graduation was not granted due to a lack of sufficiently high marks in the examinations. However, he spent two years at Bonaventure, at the local college, in 1970 and 71.

Of this time he retains a generally pleasant memory even though he was very lonely and largely rejected by the other students. Of course, it must be emphasized that he had become very independent and rarely agreed to collaborate with his teachers. However, he created an almost boundless admiration for his physical education teacher, a certain André Beckrich, on whose personality he tried to have a bit of. This so-called Beckrich of Belgian or Swiss foreign origin had served during the last war as a special commando. This alone was enough to convince Bernard of the abilities of his sports teacher who was truly a master of swimming and who would become in the following years an instructor of national reputation, at least at the level of Quebec, and he mastered the general science of physical education.

In 1972 Bernard went to Caplan, a small village located a few miles west of Saint-Siméon, to continue his high school studies, precisely in grade eleven.

There it was really a disaster. The climate of the C.P.E.S. of Caplan, the school he had to attend, made his cup clearly overflow and at a little less than half of the school calendar he began to realize that he would fail and would not be able to obtain the graduation. Let us note in passing that this C.P.E.S. was the old regional school of Gaspésie where agriculture was taught as a specialty. Due to the lack of sufficient candidates for the cultivation of the land, the school of agriculture had to be converted into a regular school.

During that year 1972, he became very agitated and could no longer concentrate on the study of the various subjects enrolled in the program. Many of the institution's directors even began to advise him to move towards a less scientific field, a manual trade or simply to spend a few years on the job market in order to gain some practical experience of life. It was also a question of letting adolescence pass and the instincts of rebellion disappear from his personality.

This last hypothesis of the job market seemed to be the most interesting for Bernard, especially since he was now 16 years old, he was starting to want to be independent of parental help and that the need for money really belonged to him and became a kind of necessity, at least according to what he thought. After a few weeks of reflection, he made up his mind. He would drop out of school and start earning a living. The problem now was where to go and what to do? Who would agree to take on this young man who, at first glance, offered nothing disgusting, but nothing so attractive either?

His family, in this case of school abandonment, had hardly felt any really precise signs of it. As for his father, Leonard, he was convinced that life is learned by living it and he had every intention of letting his sons face this life and see them fend for themselves. Especially since 1967, the family had to resign itself to send André, the one who comes between Bernard and Raynald, to a specialized institute for the deaf, an event that had strongly affected Leonard and Anita who were discouraged by the ordeal that fate was sending them. Leonard had also let his elder son take a bit of a break, at least academically, and he only watched the results from a distance.

For this reason, when he announced his intention to start working, there were practically no negative comments, except of course for the first reactions of the moment.

Leonard's main dream for his offspring was future jobs where his sons could be secure and from which they could earn enough money to support a whole family. A civil servant or a commissioner, of which there were already several around him in the Gaspé, would have been a good match for him as a father. As for Anita, like any mother who sees in her son a simple child that she would always like to keep close to her, she had nothing to say about the present events that she considered normal. At 16, you start to become an adult and if you want to raise a family one day, you have to start working and earning money.

We are talking about a family here, and it is important to understand that the environment and the time in which Bernard lived were rural. Generally, young people got married around 19 or 20 years old. Many settled directly on the spot in Gaspésie and thus ensured the succession of the family. Of course there were a few who went to the big cities, many even, but in those years 72 a good number remained in the places of their origin. Modern ideologies on married life and the revolution in the institute of conventional marriage had not yet appeared in this Gaspé region which is still, in many ways, pubescent and in its growth stage.

The decision was therefore made that the eldest of the family, Léonard Bujold, would abandon his school attendance. The decision was made in March of 1973. He was in grade eleven and he was now sure that he would make it through his current school year. He had not gotten the moon as a job, but his efforts had not been in vain. After meeting with his friends, one of them had advised him to go to the provincial labour office, which was preparing a special project for which full-time employees were needed, at least for a few months. He went to the government office in question and got one of the jobs. He became responsible for planting tree seedlings. However, let's be clear, responsible here meant nothing more than being the person who digs a hole with a shovel and then places a tree stem in that hole. Conne would say that this was not a job for a prime minister. The salary offered was about $I15.00 per week and you had to sleep from Monday to Friday directly in the forest in the camps that had been used a few years earlier by the loggers. Despite the lack of genuine interest in such a responsibility, this was a real treat for the growing teenager who was just starting out.

________________________________

CHAPTER TWO

Professional beginnings

Although planting young shrubs was relatively rewarding, it was no less hard physically and for Bernard, morally as well.

Secondly, he had experienced in the last few months what it is like to have money. He had started to frequent some local discotheques, hotels where there are orchestras. Then there was also a new idea in his mind; that of becoming the owner of a fitness gym.

|

| Photo published in the original edition |

________________________________

CHAPTER TWO

Professional beginnings

Although planting young shrubs was relatively rewarding, it was no less hard physically and for Bernard, morally as well.

He had never been an extraordinarily strong child physically. Even though he had been involved in physical training for some time, he could not be called "Jonny Rougeau". Morally, he has always been a solitary individual who does not feel at ease in any group setting. He even displays a certain shyness when it comes to seeing strangers or even people he has known for a long time.

The group atmosphere of the logging camps was not perfect for this lonely young teenager, but that would not stop him from continuing his work.

His father, for his part, was all fired up for this first job, especially since the company responsible for the project was Consolidated Bathurst, the same company for which he also worked. And it was not surprising on Friday nights, when Bernard returned home, to see Leonard lecture his son on the advantages of work, especially on the importance for a man not to be afraid of effort. Of course, he wanted to begin to show his son that he was getting older every day and that he would soon have to assume his responsibilities as a man.

Obviously the sermons didn't last long because the son would quickly leave, once he had washed up, to conquer possible young girls in his neighborhood to return on Monday morning at first light to his task of "tree planter".

It must be said that this first job was part of a government project to reduce unemployment, so there was nothing continuous about it. So once the contract was over, we found ourselves in early June 1973 and because Bernard had attended school at the beginning of the current school year he was able to get a job as a "student worker" this time for the Quebec Minister of Transport. His new responsibility was to mow the grass on the side of the road. Obviously it was nothing too complicated.

A few weeks later, when the available work period had once again expired, his father got him a job as a commissionaire at a local grocery store, the Coopérative de Saint-Siméon. He had to place the goods sold in paper bags and then go and drop them off in the customers' cars. It should perhaps be noted that he had already done this job before and for the same grocer on Thursday and Friday nights a few months earlier.

But the last days of summer came quickly and with them the time of the return to school. Bernard went to school and if possible, following his father's advice, he should try to go to a technical field leading to a professional training. A mechanic, for example.

But he had not set foot in this new polyvalent of Bonaventure that everything was negative.

First of all, the atmosphere was, understandably with his solitary temperament, more than bad.

Secondly, he had experienced in the last few months what it is like to have money. He had started to frequent some local discotheques, hotels where there are orchestras. Then there was also a new idea in his mind; that of becoming the owner of a fitness gym.

For the past few months, he had been practicing fitness with various tools that his father had allowed him to set up in the family home as well as in the garage and what he most hoped for was to have his own gym and to train other individuals commercially. A bit of a "Vic Tanny's" type of studio.

Apart from these daydreams, there was also the local grocery store where, due to the increase in customers, the decision was made to hire an additional employee on a regular basis.

The manager, Gérard Arsenault, had indirectly approached Bernard to take the available job, which did not fail to interest him in a serious and concrete way.

The decision was made on the same night as the start of the school year: he would leave school and work at the Saint-Siméon Cooperative.

According to him, it was preferable to seize the opportunity that was offered to him and work regularly, whereas with the school, there was no guarantee of an advantageous result at the end of the path.

With the Cooperative he was at least certain to receive a regular income.

In all this his father was probably the happiest.

Just think, at the age of 17 his son had a regular, full-time job, and better yet, only a few hundred feet from the family home. His mother, well, she too was happy to see her son sort of settled. However, she seemed to be the only one who could see the future and its reality through these happy events and said, "This is great, it's a good start and then in a year or two you can do something else."

This when even Bernard believed he had found the miracle gold lode that could be exploited for the rest of his life.

Especially since in this period many adults could not find a job. Everyone in the Bujold family was happy and we can say that the weather was good.

However, the situation did not remain like this for long and the first flames of interest soon cooled. Bernard was in charge of displaying prices, putting the products on display so that customers could see the merchandise, packaging the purchases, etc...

In short, a whole host of responsibilities necessary for the proper functioning of a food store.

On the whole, he did his job quite well, which was interesting, at least from the point of view that the work was indoor and not very physically demanding. However, adolescence was beginning to cease its influence on him and so he began to dream of the future and of other more promising horizons.

On the one hand, there was the hope of one day having his own gym, which still nagged at him, and on the other hand, seeing some of his friends exile themselves to the mining towns of Quebec, Sept-Îles, Schefferville and others, and return with salaries earned in a single week that sometimes reached the one he had earned in two months of work at the famous Coopérative de Saint-Siméon, all of this was choking the young food employee from within.

In June. 1974, it was on the threshold of the store, around 8:30 a.m. and by a beautiful morning sun, that he coldly announced to the manager that he would leave within two weeks. His decision was final and he would be going to Sept-lies in the future to earn his living.

In reality, manager Gérard Arsenault was not surprised. He had realized over the past few months that his new employee, now almost a year old, was dreaming more often than not of projects that were too grand for a simple store employee.

Projects that were probably unattainable, but that was not his problem and if the young man wanted to dream in color and break his back, he could not help it. He had given him his chance and too bad if he didn't take it.

We must add here the advantage of the Coopérative de Saint-Siméon, which was probably responsible for the general orientation of Bernard's future career. The atmosphere in the food store was very fraternal and for the customers, Bernard was a young man who had a job for the rest of his life, so to speak, and therefore a lucky young man. Customers could regularly be seen chatting with him as well as with the other employees and this was certainly not detrimental to the various meditations of the future parliamentary journalist.

This rural and warm Gaspesian atmosphere was also reflected in the internal work climate and even if we sometimes played tricks on each other, we all liked each other. It was therefore with a tear in his eye that he left his job as a food clerk as well as the work team with whom he had developed a strong friendship, a friendship that would remain with him throughout his life.

But at the time he had just turned 18 and with one of his childhood friends, Michel Bujold, who despite having the same family name had no family ties, they had both planned a program to board the city of Sept-Îles, boarding at work of course.

And his father, in spite of the first reluctance, had finally supported this idea and people in his family were beginning to firmly believe that the city of Sept-Îles would be an excellent place to continue Bernard's initiation to life.

It was also realized that he would never be a rural man and that he would have to earn his living as a nomad traveling from town to town.

The idea of hosting radio programs had also germinated in Bernard's mind following a trip to Shawinigan to visit one of his uncles when he noticed that the girl his cousin was to marry had a brother who was a television host. As our food clerk was on his annual vacation and he took the opportunity to meditate on his future, it didn't take much for him to say to himself: "If an individual who is the brother of the girl that my cousin is going to marry can make television, why can't I do it too? "

The brother in question is a man named Duquette who works for Trois-Rivières television, but the funny thing is that he never knew the role he played in Bernard's career.

It is with a certain disappointment that he realized that it would be impossible for him to associate with a gym owner in the Mauricie region who had suggested to our young Gaspesian that if he wanted a gym he would first have to work and prove himself a bit more.

Bernard promised himself on the other hand to attack this new crush: the radio world, and to create, if not invent the radio in Sept-Iles because of another special characteristic, like many of his friends, Bernard believed he was dealing with a world in full expansion on the North Shore and barely at the age of its colonization.

However, this was not to be the case and even though our potential discoverer would become a presenter for the Sept-Îles radio station, his adventure in the world of communications had only just begun.

Note: The uncle mentioned here is Albert Bujold who married Alice Jobin from Quebec City. The latter is the intellectual of the Elie family and Bernard was strongly inspired by this uncle who was an innovator. One could even say that Bernard is the continuity in the new generation. As for his cousin, it is André Bujold who married Denise Duquette from Shawinigan.

Sept-Iles 1974

Beginning of journalistic career

This famous adventure which was to lead to a kind of "Inca" treasure in Quebec was not so miraculous as expected. At least in the first times.

The arrival as such in Sept-Iles in July 1974 was almost historic.

Bernard and his companion Michel boarded a Québécair plane to make the trip from Mont-Joli to Sept-Iles. In addition to the fact that for our two thieves it was the baptism of the air and that Michel did not seem to take so much the balloting of the plane and that he feared at any moment that this one starts a descent towards the ground; due to the fog the sixteen passengers of the plane had to descend before destination on a landing field of fortune covered with gravel and in full forest in the surroundings of Port-Cartier.

Our valiant pioneers were not mistaken, if we were to believe the first impressions, the North Shore was really in full colonization even in 1974.

If Michel had almost not been able to resist the airplane trip while Bernard was laughing like a teenager in front of a comedy movie, this time it was him who was starting to be prey to a horrible fright.

"Listen Michel, it's awful. We'll go back to the Gaspé right away. You see that it is still at the stage of the Indians. Tomorrow morning, I'm leaving for St-Siméon. And you know, co-op is not that bad. I think I'll go back."

The reasons that mainly motivated Bernard's fears are that between Port-Cartier and Sept-Iles, there is nothing that can attest to the high degree of industrialization that the region and especially cities like Port-Cartier and Sept-Iles have experienced. The nature along route 138 is still completely untouched and in some places if the landscapes are really extraordinary they are also really wild.

And as for returning to his grocery store, Bernard saw it as an emergency exit because the manager had let him know that during the next few months, if he wanted to return, the door would be wide open. He would even wait a few weeks before finding a permanent replacement for him.

From Port-Cartier to Sept-Iles, it had been agreed that the company Québécair would pay the cost of transportation by cab to the city center. During this trip, Michel, who was quietly recovering from his flight, had also regained his composure and it was with encouragement that he reassured his companion:

"Well, listen, I know someone in Sept-Iles. Before getting discouraged, let's wait until we get there. Since the time I've been hearing about the North Shore and its beautiful jobs, let's see if it's true.

It should be added here that indeed several of Bernard and Michel's friends were supposed to work in Sept-Iles and the surrounding area and that several other people from St-Siméon had assured the two exiles that according to them the North Shore was welcoming and that employment was readily available there.

Finally, after the two-hour drive from Port-Cartier to Sept-Iles, they arrived in the promised city.

In the end it wasn't so bad except that now the fears were transferred to the other side of the coin. Now the city was much too urban and where would they find employment, these young Gaspesians who had just left their local town? At first glance, there were only a few mobile homes, commercial buildings and various skyscrapers scattered around.

Nevertheless, our two colonial soldiers settled down for a first night's stay at a hotel that turned out to be the worst in the city, at least in terms of reputation. However, the comfort level was acceptable. (It is understandable that the precise name is not mentioned here)

One of the interesting anecdotes that Bernard likes to tell is that of the "Topless" dancers, an anecdote related to this hotel. Michel and Bernard were lying in their room and were discussing things. But what a surprise it was to hear a perpetual music playing on the first floor of the hotel and not to be able to fall asleep before the early hours of the morning, around 2:30 a.m., time when the mysterious music stopped.

The next day it was Bernard who was the first to go and pay the bill for the first night's stay and to say that the double room would be kept for another night, asking the owner:

"Listen Sir, your room is not bad but the music! Couldn't you ask us to turn it down a little? Me and my colleague couldn't sleep all night."

The hotelier replied almost immediately to his two disgruntled young customers:

"Ah yes the music! Well, these are my dancers. It's a show - you know there are six a day. You should come see this. They're topless dancers you know young girls who take their clothes off... "

Surely our two young visitors would come and see this thing. Even they were the first ones to be seated around 4 o'clock in the afternoon waiting for the first show to be presented at 5 o'clock. Their joy was even greater when they learned that the famous dancer was staying in the room next to theirs. Unfortunately, in spite of the numerous plans of attack and attempts of our Valentinos they could not succeed in putting the grapple on him. What do you want? Error of youth persists to say Bernard.

But more serious tasks were waiting for them, so the search for a job turned out to be a rather difficult task.

How could the others get hired by the mining companies? After having filled out job applications with the companies, it was only fair to conclude that in two months all activities would have ceased on the North Shore. No job available for them and this at each of the companies where they had gone to apply.

We were now almost a week into our stay in the iron capital and nothing had really worked out as planned. Bernard and Michel had moved into an apartment in the city center. According to them it would be easier to wait and especially less expensive than in a hotel.

Temporarily, the husband of a cousin of Bernard's who lived in Sept-Iles had managed to find a job as a janitor for each of the two newcomers, but at a ridiculous salary and the job was only for a few hours a week.

Other than that, the situation was really dramatic.

The return to the Gaspé would be soon unless an unexpected miracle occurred. But Bernard, who had arrived there with ideas of grandeur, began to bring them out during these gloomy days.

Recovering from his first emotions, he gradually regained his natural form. The idea of the radio also resurfaced and it is a bit like the fox in the fable who studies the lion before going to engage in conversation with him that he looked and inquired about the situation of this radio in Sept-Iles. Then he decided that he would go and offer his services to the management of the radio station the next morning at first light.

In the meantime, during that same afternoon of scholarly reflection, while our two researchers had searched the city in vain in search of a job, they were calmly resting while sipping a beer in a café-restaurant located right next to the Sept-Iles radio station, Le Venise.

Sitting next to them were two other individuals who, strangely enough, were carrying a portable radio that they seemed to be listening to religiously. After listening to their conversation for a few minutes, there is no doubt that these two people work for the radio station whose building is located right next to the restaurant where they are all.

That's all it took for our valiant Bernard to strike up a conversation and ask about their exact job inside that radio "station".

"Excuse me sir, do you work for the Sept-Iles radio station?"

-Yes! Yes!

"It's funny because I come from the Gaspé and I'm here to work in radio. You see, I want to offer my services as an announcer. So tell me, in your opinion, what is the best way to approach the management, especially since I am a beginner in the business?

The two employees of CKCN radio were, among others, Jean-Philippe Perretti, today employed by Radio-Canada in Moncton, New Brunswick, and Bernard Gendron, today an electronic technician for a private company on the North Shore.

While finishing their respective drinks and continuing the discussion, Jean-Philippe Perreti, who was a presenter at this radio station, ended up advising Bernard to offer his services as an on-air operator instead. That would be a great place to start and there was nothing to stop him from aiming for something else once he was in the box.

Perreti's colleague supported this advice and pointed out that the station, which had just been moved into its new building, was currently in a running-in period. So the director needed a few operators to test the new formula, old in larger boxes but new for radio stations like this one, an announcer responsible only for the animation and an operator for the on-air.

The return to the Gaspé would be soon unless an unexpected miracle occurred. But Bernard who had arrived there with ideas of grandeur began to bring them out during these gloomy days.

Recovering from his first emotions, he gradually regained his natural form. The idea of the radio also resurfaced and it is a bit like the fox in the fable who studies the lion before going to engage in conversation with him that he looked and inquired about the situation of this radio in Sept-Iles. Then he decided that he would go and offer his services to the management of the radio station the next morning at first light.

In the meantime, during that same afternoon of scholarly reflection, while our two researchers had searched the city in vain in search of a job, they were calmly resting while sipping a beer in a café-restaurant located right next to the Sept-Iles radio station, Le Venise.

Sitting next to them were two other individuals who, strangely enough, were carrying a portable radio that they seemed to be listening to religiously. After listening to their conversation for a few minutes, there is no doubt that these two people work for the radio station whose building is located right next to the restaurant where they are all.

That's all it took for our valiant Bernard to strike up a conversation and ask about their exact job inside that radio "station".

"Excuse me sir, do you work for the Sept-Iles radio station?"

-Yes! Yes!

"It's funny because I come from the Gaspé and I'm here to work in radio. You see, I want to offer my services as an announcer. So tell me, in your opinion, what is the best way to approach the management, especially since I am a beginner in the business?

The two employees of CKCN radio were, among others, Jean-Philippe Perretti today employed by Radio-Canada in Moncton, New Brunswick, as well as Bernard Gendron today an electronic technician for a private company on the North Shore.

While finishing their respective drinks and continuing the discussion, Jean-Philippe Perreti, who was a presenter at this radio station, ended up advising Bernard to offer his services as an on-air operator instead. That would be a great place to start and there was nothing to stop him from aiming for something else once he was in the box.

Perreti's colleague supported this advice and pointed out that the station, which had just been moved into its new building, was currently in a running-in period. So the director needed a few operators to test the new formula, old in larger companies but new for radio stations like this one, an announcer responsible only for the animation and an operator to put it on the air.

Normally, in most stations, the announcer is responsible for both the on-air presentation and the animation. In Sept-Iles, the management of CKCN radio had decided to split the on-air and the production. The operator had the task of broadcasting at the scheduled time such and such a recording prepared in advance on tape.

This was the kind of responsibility Bernard had to ask of the radio station management.

Bernard was quick to offer his services. It was to the general manager at the time, a certain Raymond Perreault, that he presented himself to make his first direct attack. The latter, warm and welcoming; relations were not always to remain so between Bernard and him, admitted that the idea that was proposed to him was excellent but added:

"Radio operator is not a man's job. Here we hire mostly women or students for this task. The reason is that the budget for this service is not so high, so the wages paid are not so extraordinary. About sixty dollars a week. It's a great source of second income but not a living. Look, get a job in the city and then come back to me. As soon as you get something you call me and you can consider yourself a Sept-Iles radio operator."

Bernard was very happy with these kind statements and did not fail to mention the possibility for him to be a presenter for this same station one day. A day that meant as soon as possible.

Again, the director, Raymond Perreault, was not negative and reassured him that it happened often. Individuals would come in for a voice test and if the result was acceptable then the candidate was hired. In this case, he emphasized that we could talk about it again in the next few weeks, but that the important thing was to find a job elsewhere in the city on a regular basis. After that, we could work out a collaboration plan according to the availability of each one as much for animation as for broadcasting.

Bernard was crazy as a broom. Just think, the director of the radio had received him in his office and had even closed the door for more privacy. Then, far from being negative to the offers, he had admitted that they fully met his current needs.

In the evening, he proudly told his friend Michel, who didn't believe him and told him to be careful, that maybe the director had simply made fun of him.

Come on, thought Bernard, how could anyone have such ideas? The station manager was such a warm and polite guy.

Of course he had rounded the corners and interpreted the interview to his advantage, but the station manager really needed staff.

In small stations there is a high turnover of employees and you have to be able to fill the gaps quickly. Bernard's offer was like that of any newcomer to radio, a bit delusional but who isn't? And when the time came to cool down our young "Henri Bergeron" in power, it would not be difficult and it would only be necessary to dot some i's.

In the world of radio, we often have our feet on the ground, but we also have to be daring, almost dangerously so, in order to obtain good results.

If there is one field where routine has no place, it is the world of radio and television. Inside, the director must have known this too.

The famous job that would allow him to enter Sept-Iles radio was not an easy thing to get. There was a janitor's job, of course, but the hours were evenings and nights, the very time when our radio director planned to use our newcomer.

We had to wait about two weeks before he was able to tell the CKCN boss that he had a regular job with a daytime schedule. He was a regular salesman for ROCO Inc. a firm specializing in the sale of construction materials to the private sector, including local mining companies. Iron Ore of Canada, Wabush Mines, Rayonnier Quebec, etc.

Now we could seriously discuss the Bujold-CKCN association. However, in reality the job at ROCO Inc. was not obtained with folded hands. It was with his cousin, Louisa Bujold, and her husband, Jean-Claude St-Onge, that he had finally agreed to apply for a position with this merchant.

Louisa Bujold is the daughter of Germain Bujold, Leonard's brother, who married Fernande Bergeron.

From the outside the building was not so comforting and there was also the fact that the perpetual embarrassment, which is characteristic for Bernard in front of new events, was not totally absent. Whenever he has to do things he is not used to, he always wonders if he has gone a little too far and if he will be expelled.

However, once inside the building, he had regained his confidence and it was with energy and enthusiasm that he tried to sell his salad to the manager of this sales firm.

The manager in question, Mr. Elysé Lanteigne, took him a little pity and, as if he saw in him one of his sons, he undertook to integrate him into the company. He told him to wait a few days to plan things but that there was a good possibility that he would be hired.

Four days later, almost totally discouraged, Bernard heard the doorbell ring. He was asked to come and answer the phone at the reception desk because he had a call. Surprised, he went to the reception and was even more surprised to hear the director of Roco Inc. with whom he had spoken a few days earlier, tell him that he had been hired.

Not knowing how to thank his new boss, he stammered a thousand thanks and then went back to his apartment to wait for the return of Michel, who had found a job as a welder a few days earlier, a very lucrative position.

The director of CKCN, Raymond Perreault, again warmly welcomed our new hardware salesman and he began as promised to establish a possible work schedule as an on-air operator.

As for the announcer thing, well, he had frankly pointed out that for the moment we had other things to worry about and that it was better to wait a while.

It was therefore decided that Bernard would be an operator during the hours of 6 a.m. to midnight and that on Thursdays and Fridays when he was held up at the hardware store, he would be compensated by Saturdays and Sundays. In all a period of responsibility of 30 hours of broadcasting per week.

Obviously, the full work schedule was becoming burdensome, but he was confident that he would have no problem keeping up.

Indeed, everything went relatively well. He started at 8:30 in the morning as a salesman at Roco Inc. and in the evening after 5:30 he went directly to the station to keep the broadcast going until midnight.

The anecdote that recalls this time and that Bernard likes to tell is that of the "water jar".

It is understandable that after finishing his shift at midnight, he was not so much asleep since for a human being the most difficult hours to stay awake are those between 9 am and midnight. Also in the evening it was not uncommon to see our radio operator storming into the apartment and making a racket in front of his friend Michel's bedroom. When this one did not wake up, our knight of the night took care of it by opening the door of the room and by tipping directly the mattress of Michel on the floor. The latter, ejected from his bed, would wake up all surprised believing he was having a horrible nightmare.

As soon as he came to his senses, Bernard said to him with candor: "Michel, what would you think of going for a little beer to pass the time. "

Poor Michel could not believe his ears or his eyes. He had to get up at five o'clock in the morning to go to work in his welding shop, but now he was woken up at one o'clock in the morning. Really, if he hadn't known the intruder, he would have thrown him out the apartment window.

But on a good night Michel set out to catch our troublemaker in his own trap. With the help of wire and a margarine container, he installed a system that would normally cause water to fall on whoever opened the bedroom door from the outside. Proud of his invention, Michel went to bed that night with his soul at peace and convinced that if he was dragged out of his sleep at least he would have a good laugh.

Unfortunately for him, the system did not work as planned and when Bernard arrived and noticed that the bedroom door seemed to resist opening, he thought that it was only a chair placed in front of it that prevented it from opening. He immediately undertook to open it by force because he said to himself that it was necessary to wake up the individual lying in this room because every evening it had become the golden rule of the establishment. After a few presses, the door not only unlocked but also came off its hinges and fell to the floor without the shower system working. Michel was once again awakened from his sleep but Bernard had not been punished.

Needless to say, when they saw all the paraphernalia hanging from the ceiling, and especially when they saw how the events had turned out, our two friends took the thing in stride and went to have a midnight beer that evening.

In the meantime a vacancy was going to be created at the radio station where the newsreader responsible for the evening and weekend bulletins had just left. Bernard, who had befriended the news director, a certain Réal-Jean Couture, undertook to win him over and convince him to take on this responsibility.

Bernard saw an opportunity to become the anchor he had originally planned to be. The general manager, however, did not see it the same way and was not convinced that Bernard was the man he needed and categorically refused to give him the responsibility of newsreader.

Our on-air operator had only been at the station for a month, having been hired at the end of July and now in early September, and that was not enough time to have made a judgment on his general personality.

However, while this director was out of town on business and Bernard had totally won over the news director, Réal-Jean-Couture, this person in charge decided to entrust the narration of the current weekend's news bulletins to his new friend.

After two or three bulletins, Réal-Jean Couture, very proud of his prodigy, congratulated him and assured him that on Monday morning he would go and announce to the general manager that the evening and weekend news reader had been found and that his name was Bernard Bujold.

During that Saturday afternoon, our two comrades could be seen driving around the city in their respective cars in search of information on a supposed demonstration by the local Indian reserves.

It is worth mentioning that Bernard had bought a car, a 1969 Ford Marauder, a luxury model that was obviously a few years old.

But the exuberance of the weekend was not to last long and what a surprise it was for Bernard on Monday morning to receive a call from the general manager of the radio station and to hear the latter yelling at him at the other end of the line. He was expecting congratulations and was waiting for this call to confirm his commitment as a newsreader. He was wondering which saint to turn to.

"Are you crazy, C... who is the boss here? Who gave you permission to read news on the weekend while I was out of town?

Bernard, all disconcerted, tried in vain to explain that it was the director of information who had given him this permission and that he had promised that the position would be given to him permanently.

The director, Raymond Perreault, was quick to deny the alleged promises of his chief reporter and continued to lecture him on the serious crime, in his words, that his overly enterprising on-air operator had just committed.

White as a sheet, Bernard hung up the camera and tried to resume his work as a hardware salesman.

Having somewhat regained his composure and following the encouragement and advice of his co-workers in the store, he decided that he would not remain humiliated. He would resign from CKCN Radio as a sound operator.

So he called the manager back and said:

"Mr. Perreault, I no longer work for you. I didn't like your attitude and I want you to know that I'm not a person who can be thrown around like a ball. Find yourself another operator because for me CKCN is M...."

Perhaps more surprised than Bernard at the first call of his boss, the latter remained speechless in front of this surprise statement contenting himself to say that it was okay and that he accepted the departure of his supernumerary employee.

In the meantime, our news reader for a day had seen the news director again as a friend and told him in detail about the latest events. Disappointed by Bernard's latest move, he invited him to reconsider his resignation and promised that he would make things right.

"Listen to me, give me until tomorrow. I'll talk to Raymond Perreault and I swear to you that I will make things right. You will be my news reader, I promise you.

With these encouraging words, Bernard decided to accept especially since inside he was beginning to regret having acted a little impulsively. He would have liked to return to the radio station and especially to become the news anchor. So he returned in the hope that Réal-Jean-Couture would really fix things and indeed things did get fixed.

No one knows exactly how, but eventually Raymond Perreault agreed to let Bernard return to the station and was even willing to allow Bernard to take a voice test to replace the necessary newsreader. The test in question was the simulated narration of a short two-minute news bulletin that had to be recorded on tape. He passed easily, at least according to Réal-Jean Couture's comments, and our young Gaspesian then became, at the beginning of October I974, at the age of 18, the official newsreader of the CKCN radio during the evening and weekend schedules.

At the time, he had some very personal characteristics. One of them was the way he pronounced his name: Bernard Bujolde and by pressing the last syllable of Bujold he pronounced "olde".

Another peculiarity was his Acadian accent, which did not show up during his on-air readings, but he spoke fluently with this accent in his voice, like the Edith Butlers do.

However, nothing at all came out during the narration of short stories because he had found a method that by forcing his voice gave an almost neutral sound to his diction.

Bernard was really happy and probably even happier because he now had a responsibility that no one in his family had ever had before except perhaps Geneviève Bujold, a film star with whom he had family ties but indirect descent.

He was very proud as a Gaspesian to have gone beyond the limits and to have become partially a radio presenter.

Everything will be fine in the best of worlds until February of the following year, some five months later. On the one hand, the job he had at Roco Inc. was in a way contractual. In the sense that at the time of his hiring, the director, Elysé Lanteigne, had warned him that the company would close its doors in February. Thus, work could only be assured for the few months preceding the February closure.

With the arrival of that day, he also saw the scenario of last summer when he had to look for a job and the memory of the many doors closing in front of him also resurfaced.

Nevertheless this time he would have more chances on his side because the work of these last months had allowed him to meet many people of the business world and they had all promised to help him to start again to the work plan. Several had even made concrete job offers.

But when you are young, you have to learn and this initiation is often expensive.

Most of the job offers made to Bernard came from the life insurance industry. Bernard's verve and interpersonal skills were of great interest to many brokers who were convinced that he would make an excellent salesperson in their organization.

Unfortunately for him, not everything was so simple. Bernard's need for security when faced with a new situation or new people was the primary cause of his problems. The simple fact that the salary of an insurance salesman is conditioned by the number of sales made and that the weekly pay is never fixed worried our young job seeker so much that he finally decided to accept the least attractive of the offers he had received but also by far the safest. He became a salesman for a car parts company. It was a branch manager of an American company, United Auto Parts, better known as U.A.P., who offered him the job. This manager, a man named Robert Lavoie, had met our friend by chance at the hardware store and had openly proposed that he become one of the salesmen on his team.

The reassuring and actually undemanding aspect of the offer had seduced Bernard who accepted it a few days later.

And his father, who continued to guide his son from a distance, was one of the first to advise him against getting involved in the world of life insurance. According to him, there was nothing good about it and his son should look at the more financially solid side of the established sales business. Auto parts were fully within the scope of his plans and he did not hesitate for a moment to push into the arms of this Robert Lavoie, manager of U.A.P. in Sept-Îles.

Bernard would never regret a decision as much as this one. And curiously enough, he would remain employed by this company for more than a year, pondering his unfortunate fate and having all the trouble in the world to get out of the straitjacket he had created for himself. The job as a salesman for U.A.P. was a total failure mainly because he was too preoccupied with the idea of climbing the ladder of the radio world.

But the worst part came when the manager of CKCN told him that the station management had decided to terminate his services as a newsreader.

The reasons? There were none in particular, except that changes had been made in the overall programming.

What disappointed our unfortunate budding journalist even more was that there was no indication of such a move. A few days earlier, the same Raymond Perreault had talked to him about the possibility of becoming a regular presenter, an idea to which Bernard had attached himself and which he had been lulling in his mind because in his job as a salesman everything was going wrong. And now, without warning, he was told that the responsibility he held most dear was simply taken away from him.

The world could not have ended more tragically.

In reality, however, such a move could have been foreseen. First of all, for some time Bernard had been experiencing problems with his voice, mainly with his vocal cords, not so much with his Acadian accent but rather with his biology. It was not so much his Acadian accent but rather biological problems. He had difficulty placing the intonations on the right level of resonance and often some of the words spoken were inaudible.

We can also assume that Raymond Perreault had not forgotten the spat he had had with him a few months earlier and if he had agreed at the time to take him back on the team, it is surely because there was one or more unknown reasons related to the famous meeting between Couture and himself, Raymond Perreault.

At the same time as his dismissal from CKCN, exactly on February 9, 1975, the situation was getting worse and worse at U.A.P. and the manager Robert Lavoie finally had to admit to his young salesman that according to him, he was not made for the work in the car parts industry.

Her lack of interest was too obvious and he advised her to find another job that would better suit her personal goals as well as those of the company. Why not go back to school," he suggested, adding:

"If you're interested in radio, man, why don't you go? Surely there must be schools that teach this kind of work."

"And you know what's important in life is to do what you love. It's obvious you don't like it here. It's not your fault you're made that way."

But the unfortunate events were too fast for Bernard's ability to resist. Seeing all the calamities coming down on him, he clung to this last job as a salesman and undertook to show that he was interested in this responsibility in the automobile. He used the excuse of the various problems that beset him and promised that in the future he would put a little more heart into his work.

The manager agreed to give him another chance and allowed him to remain on his sales team. However, during the following months, even if he had succeeded in satisfying the management of U.A.P. as a salesman, his soul was not there and will never be there during the rest of his stay at this company. Our young martyr of the radio will meditate on his bad fortune and will look for a miraculous solution. A solution that will come, but very slowly and with great difficulty.

Bernard gradually recovered from his emotions and started his sports training again, mainly at the Sept-Iles municipal gym.

As the weeks went by, he also regained confidence in himself, and in his mind, future projects began to surface. Soon he would force his fate again and succeed in getting a job in organized sports as a physical education coach. This would be his stepping stone as he desperately tried to find out why the jinx had hit him for the past few months.

He eventually figured it out. If he ever wanted to succeed in life and get through the obstacles of this one, he would have to learn to get rid of this feeling of fear in front of the challenges and he would have to be able to go headlong sometimes. There was no place on this earth for those who are afraid to dare in front of the unexpected.

He would make this sentence his basic principle.

________________________

CHAPTER FOUR

Fitness Instructor and Chronicles

SportSanté

It was in June 1975, at a time when Bernard Bujold was meditating on his situation and trying to analyze it, that the destiny he would have to fulfill less than three years later by becoming a parliamentary journalist at the National Assembly of Quebec took shape in a more visible form.

A destiny that had been in the making for some time, but which, like all heavy destinies, would have to undergo a life initiation at a more than accelerated pace, and would often be presented before its end.

His job as a salesman at U.A.P. allowed him to have several moments of free time. He did not waste these periods and tried by all means to straighten the boat for which he was responsible and tried to find, even in this city of Sept-Îles, people who would accept to give him another chance in the professional world and if possible in the radio world.

Indirectly, he would get this chance from a local promoter, Guy Marcheterre, president and owner of a local advertising agency.

But before that, he would have to return to the world of sports where he had excelled a few years earlier as a participant; in particular as a boxer (this pugilist career never went beyond the amateur stage, because Bernard himself finally realized that it could be dangerous for him to push his participation in this sport too far, given his rather average physical constitution. )

This time he would be a sports trainer.

For a few months he had been training almost daily with weights in the company of other employees of the City of Sept-Îles and he became very close friends with an animator from the Service des Loisirs, a certain Laurent Imbeault. The two of them agreed on the definition of sports principles and had also created a mutual respect. Bernard finally confided to Laurent one day that he didn't like his job as a salesman at U.A.P. This responsibility of selling junk cars made him sullen and as soon as he could find something else, he wouldn't hesitate for a moment and he would make the jump.

It must be said that by the standards of the automotive market, the parts sold by U.A.P. were of excellent quality, but for Bernard it was all the same and he considered it to be junk.

One of the areas where he would have liked to distribute his professional services was organized sports. He wondered if he was not destined for a career in recreation and if he would not end up becoming the gym owner he had thought of becoming a few years earlier. So he had no hesitation in pointing out to his new friend that if he could find him any responsibility within the Recreation Department, that he would accept it immediately. The position offered did not have to be a director's position. Anything would do, and once he was in place he would soon demonstrate his ability and potential in organized sports.

An opening was indeed available, in fact many were, but in many cases the responsibilities to be filled were unpaid tasks. However, a position for an athletic trainer specializing in weightlifting was on the list of hiring needs in order to be able to carry out a new program in the Municipal Recreation Department's activity calendar. Work for which some form of remuneration was granted.

Laurent whispered to Bernard, "I think I have something for you. Responsible for a group of young people to train them to compete in weightlifting. Are you interested? "

He was certainly interested. However, there was a problem. He had some experience in weight training, but weightlifting was different. This discipline consists of lifting a weight above one's shoulders. The weight is fixed on a bar and the one who lifts the heaviest weight wins the competition. Often the weights reached are between 400 and 500 pounds.

Poor Bernard, who weighed only about 125 pounds, wondered if he would not be ridiculed in this new role.

Nothing better to know than to try and see what it was like.

Nevertheless, he prepared himself well for this new task and on the following Monday he contacted the Weider companies with whom he had kept some contact and asked them to send him all the available documentation on weightlifting. In addition, he spent the evenings leading up to the curtain call with his new students, leafing through and studying a number of books on the mysterious discipline of weightlifting.

The famous night of truth was finally a success. The group of supposedly strong men was composed of about twenty young teenagers with a reassuring physique and no resemblance to that of an "ice-cream cabinet".

The participants who had registered for this activity had done so more out of curiosity or to pass the time than anything else. Bernard could therefore confidently begin explaining the supposedly secret principles of the mysterious weight lifter.

His interpersonal skills and ease of contact were not a handicap when approaching the participants. He even occasionally used his Acadian accent, which amused the group.

These young amateur athletes saw him as a normal trainer and had no questions about his physical size or previous qualifications. They themselves were only 15 or 16 years old on average.

Many even became good friends with him. He was a bit more aggressive about this friendship when he realized that several of his students had sisters who were quite attractive and also seemed to have interesting personalities!

"You have to make the most of your friends," he often told his students.

There were no major problems in this weightlifting class. Prof. Bujold had done his homework and with his personal experience in amateur sports, he was able to organize a course program that followed well and that would lead to a basic mastery of this discipline. The experience was so successful that our expert decided to expand the scope of the program in a very important way.

The idea came to Bernard during a day off when he had spent the morning at his apartment, in order to put some order in the house which was beginning to look more like a boat in distress than a boarding house. Let's add that his friend Michel had moved into his own apartment a few months earlier, which meant that Bernard had to take care of this large apartment on his own, which he had started to occupy as soon as he arrived in Sept-Îles.

As he listened absent-mindedly to his television set, he paused for a moment to catch his breath. The program being broadcast was a series on food with the well-known host Juliette Huot. She was hosting guests and experimenting with various recipes that, according to the reaction of the participants, must be excellent to taste. Suddenly Bernard had the shocking idea, which would later turn out to be really interesting, that the hosting of columns on weightlifting could just as well be done as he was doing on food, columns that he was currently seeing on his small screen.

We could even broaden the scope of the program and extend it not only to weightlifting, but to the whole field of sports by making scientific comparisons. This research could be presented in the form of a daily program. The idea seemed interesting and worth trying to realize.

Back at work the next day, he hurried to contact a local publicist who he knew was affiliated with a radio station in Sainte-Anne-des-Monts. The latter was to regularly find clients willing to advertise their products on the radio station in question.

Bernard did not know this publicist personally, but he used his sales skills to break the first ice. He didn't beat around the bush and proposed his project of radio programs on sports directly to the agency director, a certain Guy Marcheterre, then president of Publinord. He submitted the idea by presenting the content of the eventual program as being the result of research on organized sport and physical health. He envisioned a series of ten or fifteen programs, each four or five minutes long, produced and hosted by Bernard Bujold, a fitness expert and former newsreader for the local radio station.

He even added that if a sponsor could be found to pay for the broadcast, he would not personally demand any percentage for the production.

The manager of the advertising agency, a small agency which, while being very functional and providing its owner with attractive revenues, had only one salesperson in addition to Mr. Marcheterre himself and a secretary who acted as a telephone operator and was responsible for correspondence.

The manager gladly accepted the proposal, or at least the general idea, but he also wanted to take advantage of it. He suggested to Bernard that he let the project sit for a few days at the most, to allow him to find a sponsor who would pay for the broadcast.

The two men agreed to meet again in the next few days, three or four at the most, and that in the meantime they would each work on their own to find a charitable financier.

No one knows if our advertising magnate was diligent in his search for a sponsor for the program, or even if he really took the idea seriously, but Bernard put all his efforts into finding the necessary merchant. Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

It was September 1975 and since his services had been more than appreciated during the weightlifting sessions, Laurent Imbault had asked him if he would be interested in taking on the role of fitness instructor during the next session of the Municipal Recreation Department. The group of students this time would be adults and the subject would be indoor jogging.

Each season, there were many participants in this activity and over the years, the City's management had to divide the participants into two different groups. One group would come to train at six o'clock in the morning and the other would take over an hour later at seven. During these sixty minutes, under the direction of an instructor, twenty or so men and women would undergo a complete physical conditioning session ranging from various stretching exercises to running for the last ten minutes.

Bernard gladly accepted such a responsibility, especially since he was usually a real physical education teacher or an individual highly qualified in a health discipline.

The year before, it was a man named Denis Aurey, a career physiotherapist who had left his work in health to take on the management of the Sept-Îles arenas. It was therefore quite an honor for Bernard to take on the position of sports coach. And if our young Gaspesian had no real training in physical education, he did have a good knowledge of physical activity, being himself a fitness enthusiast, and he wasted no time in developing a complete and well-structured program where participants were subjected to various beneficial exercises.

Presumably, everything would be fine. However, our young teacher would not have to take care of the animation of this course alone.

In conjunction with the Adult Education Department of the Sept-Îles School Board, the Recreation Department had decided to offer only one morning jogging class. It was decided to partner with each other and present the program in one location. Bernard would be coached by a teacher from the school administration who was a highly qualified physical education teacher after many years of study at the university and for whom the respect of principles was not the least important. For him, physical activity should be the responsibility of people coming out of universities and one could not pretend to master the sports techniques by a single direct contact even if the individual put the best will in the world or was gifted with the most beautiful possible aptitudes.

However, our scholar accepted, willingly or not, Bernard's presence and even went so far as to give him friendly advice and guidance during the first contacts with the group.

The two colleagues shared the schedule and it was decided that he, Hermel St-Amand, would take care of the first session, the six o'clock, and that Bernard would have the seven o'clock.

Everything went very well. It must be said that once the rhythm of the first session was obtained, the presentation of the others was a piece of cake.

Bernard saw it as a form of animation and to have to support the participation of a group for a whole hour only added to his interest and increased his knowledge in the art of public communications and indirectly in radio, which he had not forgotten.

During these sessions he once again befriended a businessman who was the owner of a subsidiary of Canadian Tires Corporation which was located in Sept-Îles. This individual had enrolled in a fitness class to get back in shape. The latter, a certain Jeffrey Frenette, got along well with Bernard, but he did not overflow with a simple friendly hello or a how are you doing?

Nevertheless our salesman did not leave things there. He took care of Mr. Frenette personally and even more so when he saw in him the possibility of a financier for his sports program. Why didn't he take advantage of this opportunity and combine the useful with the necessary. A Canadian Tire store, like most merchants, needs direct advertising. It would be easy for the store manager to direct some of his advertising to the sports program and it wouldn't cost him any extra money in the end.

One morning our young friend made up his mind and told the manager of Canadian Tires directly that he had an interesting offer for him. He had a local broadcasting project in mind and the station that was willing to broadcast it wanted a sponsor. Since his store was already a customer of the station, he said he thought Canadian Tire could be the financier. The manager was not negative. He even agreed to meet with the salesman from the advertising agency, Guy Marcheterre's, and if we could agree on the costs, he would agree to support the program project monetarily. At least that's what he suggested.

The Canadian Tire manager and the agency manager did come to an agreement, but it was slightly different from what Bernard had envisioned. The original plan was for the series to be produced free of charge. The sponsor would only have to pay for the broadcast costs in exchange for advertising. The agreement that was officially concluded stipulated that the series, instead of being of ten or fifteen programs, would be unlimited, at least for an initial period of six months and then the contract was renewable, and the most interesting part of the whole affair; it was decided to grant a remuneration to encourage the young producer in his work.

The latter was of course very happy with the turn of events and it is certainly not him who would complain about the fact that he was granted a form of remuneration for this work. It must be said that the remuneration was not very high, but it underlined the professional side of his activities in organized sports and radio.

It was then decided that the series would be called "Sport Santé". The broadcast time was set for seven forty-five in the morning, an excellent time if one takes into account the arrival at work of workers or office employees. The duration of each column should be one minute and at most two minutes. It would be broadcast daily from Monday to Friday.

The first presentations of Sport Santé on Sainte-Anne des Monts radio were quite successful, although it took a while to get the hang of it. The main problems were in the sound production which was not very faithfully reproduced. Bernard was using a personal tape recorder which was probably not of good quality, because after he got a new one, the tone problems almost disappeared.

It is perhaps important to underline that the radio programs were prepared and recorded in advance on magnetic reels. Generally, about 30 programs were recorded on a single reel, which allowed for better planning by CJMC technicians. Apart from the slight technical problems at the beginning, everything went well.